- Summary of post content

- Problems with Total and Permanent Disability (TPD) insurance in super

- How the use of restrictive TPD definitions has changed over time

- The prevalence of restrictive TPD definitions in 2020

- The main groups of people impacted by restrictive TPD definitions

- Increasing detriment in a time of heightened unemployment

- Industry responses

- Conclusions

Summary of post content

- Around 10 million people hold Total and Permanent Disability (TPD) insurance through their superannuation.1

- In 2019, ASIC found some TPD policies require people who are unemployed or work limited hours per week to claim under restrictive definitions of TPD such as “Activities of daily living” (ADL).2

- The ADL definition has a much higher declined claims rate than the standard TPD definition (60% vs 12%).

- People forced to claim under the ADL definition generally pay the same premiums as all other policyholders.

- We analysed the TPD insurance policies used by 31 large super funds3 over 12 years from June 2009 to May 2020.

- As of April 2020, 30 of the 32 policies in our sample (collectively insuring 7.8 million people)4 use ADL type definitions and apply them based on a person’s work status.

Problems with Total and Permanent Disability (TPD) insurance in super

What is TPD insurance in superannuation for?

Total and Permanent Disability (TPD) insurance provides financial support, usually in the form of a lump-sum payment, to people who become disabled and as a result can no longer work to provide a retirement income for themselves or their family. Super funds are required to offer TPD insurance on an opt-out basis to most people who ‘default’ into a super product.5

Discrimination based on employment and hours of work

When a person seeks to claim on the TPD insurance policy they hold through super, they must satisfy the insurers definition of total and permanent disability. If the person is employed at least 15 hours per week and not working in a ‘special risk’ occupation when they become disabled, they can generally claim under the “standard” definition of TPD.

If not, the insurer may require the person to meet one of the restrictive definitions in table 1.

Table 1 - Key total and permanent disability definitions

| Definition type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Standard - ‘any occupation’ | The person is unlikely ever to work in any occupation for which they are reasonably suited to by previous education, training or experience. |

| Restrictive - Activities of daily living | The person cannot perform a subset (typically 2 or 3) of five basic activities associated with functional independence in daily life. The activity categories are: dressing/bathing, eating, ambulating (walking), toileting, hygiene |

| Restrictive - Activities of daily work | The person cannot perform a subset (typically 2 or 3) of five basic activities associated with work. The activity categories are: mobility, communication, vision, lifting, manual dexterity |

What is ‘restrictive’ about ADL type definitions of TPD?

These definitions overwhelmingly focus on a person’s ability to perform basic physical tasks. This makes them hard to satisfy for two main reasons. Firstly, an increasing number of claims are for mental health conditions that won’t necessarily manifest in a physical test. Secondly, most people’s jobs require them to do much more than go to the toilet or bathe themselves. So, while the test might not find they are disabled, their disability still prevents them from working.

ASIC found that ADL type definitions have a much higher declined claims rate than a standard TPD definition on average (60% vs 12%). This rises to 77% for mental health claims. Policyholders whose employment status limits them to claiming under a restrictive TPD definition pay the same premiums as all other policyholders, although the policy is of little value to them as they are unlikely to successfully claim.

Super Consumers highlighted the impact of being forced to claim under a restrictive definition of TPD in ‘Wayne’s story’. Truck driver Wayne was forced to (unsuccessfully) claim under an ADL definition of TPD because his occupation was listed as ‘hazardous’ by his insurer, although his insurance had been provided through his employers super fund.

Super Consumers has also recently published an explainer article which summarises the major issues with discriminatory TPD policies in the context of the insurance industry’s recent announcement of temporary relief for policyholders (see ‘industry responses’ section below for further information).6

Widespread recognition of the problem

Restrictive TPD definitions in super have been identified by ASIC, the Productivity Commission7 and the Financial Services Royal Commission8 as causing consumer harm. Together with the Financial Rights Legal Centre, we highlighted the detriment to people caught out by restrictive definitions in a joint submission to the Treasury consultation on implementing universal terms for insurance in super.9

Our research

Our research is the first attempt to quantify how widespread the use of restrictive TPD definitions in insurance policies bundled with default super products is and to which groups of people they apply.

Research questions

We sought to answer three key questions:

- How has the use of restrictive TPD definitions evolved over time?

- How many policies currently use restrictive ADL type TPD definitions?

- Which groups of people are required to claim under restrictive definitions?

Data sources

We sourced a data set containing the main features of the default and personal TPD policies offered by 31 of the largest super funds from the consultancy firm Rice Warner. These funds collectively cover more than 75% of default product holders and 70% of default TPD policyholders throughout the MySuper period (2014 onwards). The policy features were collected annually from June 2009 to June 2019.

We also analysed the same funds current default policies (as of May 2020) using the most recent insurance guide available for each policy. There are 32 policies for the 31 funds as one fund has multiple default products. Please note all analysis presented below is attributable to Super Consumers alone.10

Methodology

We classified policies based on the standard and alternative definitions of total and permanent disability in the insurance information document (which was incorporated in the data set) offered by the fund. At a high level, this was done by identifying terms associated with particular definitions and terms. For example, the wording “Activities of daily living” was reliably associated with policies that applied an ADL definition for some groups of people. To read more about our methodology, click here.

How the use of restrictive TPD definitions has changed over time

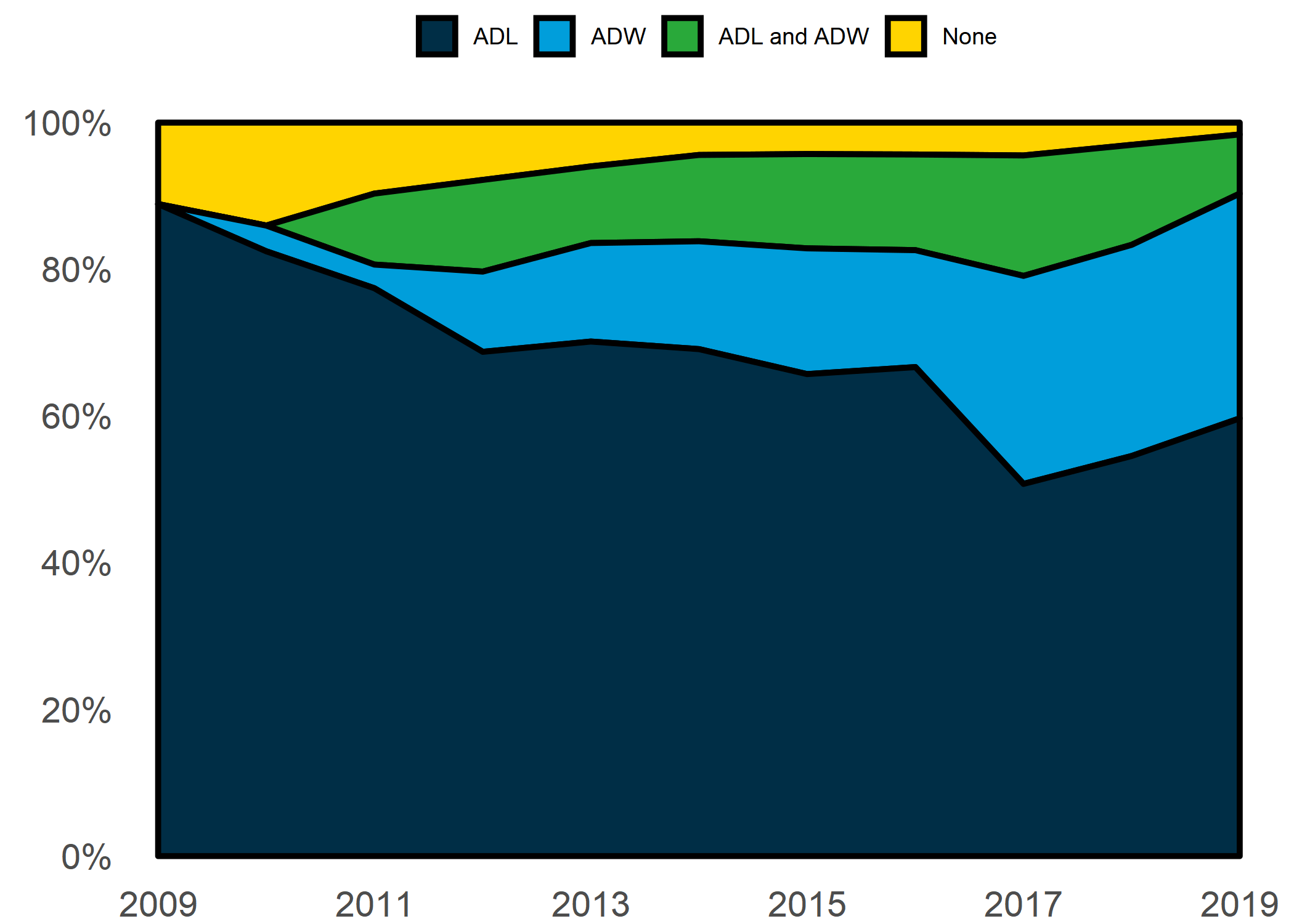

Figure 1 - Proportion of sample with ADL type definitions by sample year

Figure 1 shows near complete coverage of sample policies throughout the 11 years of policy data from Rice Warner.

Given ASIC’s estimate of three people per day being assessed under an ADL definition, this represents a long term, substantial detriment to consumers.11 This detriment is likely to become significantly worse due to the impact of the global pandemic on people’s employment (see further discussion below).

The prevalence of restrictive TPD definitions in 2020

We found that as of April 2020, only one policy in our sample didn’t apply any ADL type definition (see table 2). We also found a substantial minority of policies use the restrictive “Activities of Daily Working” definition (defined in table 1).

Table 2 - Sample policies by restrictive definition type, 2020

| Definition type | Policies | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADL only | 18 | 56.2% | 56% |

| ADW only | 11 | 34.4% | 91% |

| ADL and ADW | 2 | 6.2% | 97% |

| None found | 1 | 3.1% | 100% |

The main groups of people impacted by restrictive TPD definitions

Table 3 - 2020 policies that require a particular group to claim under restrictive TPD definitions

| Group | Policies affected | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Unemployed people | 30 | 94% |

| People working less than set hours per week (also applies to unemployed people) | 15 | 47% |

| People working in a ‘special risk’ occupation | 5 | 16% |

Unemployed people and those working limited hours per week (typically less than 15) are the main groups required to claim under restrictive definitions of TPD by terms in the insurance policy. Of the 32 policies in our sample, 30 restrict their ability to claim under the standard TPD definition - substantially reducing the value of the policy. These 30 policies currently apply to 7.8 million people who hold them through their default super product.

Five policies use an additional restrictive term - forcing people who work in what insurers define as “special risk” occupations to claim under a restrictive TPD definition.

Discrimination towards the unemployed

The majority of policies in the sample (56%) include a term that requires unemployed people to claim under a restrictive TPD definition. The term specifies how long a person must have been unemployed on the date they become disabled before they are required to claim under a restrictive TPD definition.

There is substantial variation in how long the person must have been unemployed - table four classifies the policies by the number of months a person may be unemployed at the date of disablement before they are required to claim under a restrictive TPD definition.

Table 4 - Types of employment eligibility criteria

| Months unemployed | Policies | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| less than one | 3 | 9% | 9% |

| 3 | 1 | 3% | 12% |

| 4-6 | 7 | 22% | 34% |

| 12 or more | 7 | 22% | 56% |

| Not applicable | 14 | 44% | 100% |

Table 4 shows some policies require a person to claim under a restrictive definition should they have become unemployed less than one month before becoming disabled. The most common periods are six and 12 months.

Discrimination towards those working limited hours

Nearly half the policies (47%) include a term in the TPD definition that requires people working less than a specified number of hours per week to claim under a restrictive TPD definition. As the unemployed are by definition not working any hours per week, these terms also apply to them.

Table 5 - Types of minimum hours eligibility criteria

| Minimum hours per week | Policies | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 7 | 22% | 22% |

| 15 on average | 7 | 22% | 44% |

| 14 on average | 1 | 3% | 47% |

| Not applicable | 17 | 53% | 100% |

Table 5 classifies policies by the type of hours based restriction they apply. We can see that 15 hours is the most common amount and that a significant fraction of policies moderate the requirement by assessing it “on average” over some period leading up to the date of disablement.

The most restrictive of these policies, bundled with a default super product from Suncorp, requires the person to be employed for 15 or more hours per week “on a permanent basis” in order to claim under the standard TPD definition. The definition of permanent basis excludes casual employees who have been employed for less than two years, further increasing the likelihood a policy holder would be required to claim under a restrictive definition.

Discrimination towards ‘unskilled’ workers

We identified five current policies that discriminate against people who work in certain occupations. Two of the policies that include these terms (bundled with default super products from IOOF and Asgard) exclude all unskilled workers from claiming under the standard TPD definition.

Increasing detriment in a time of heightened unemployment

The affected population is large

94% of the 2020 sample policies contain terms that require the unemployed and/or people working limited hours to claim under restrictive definitions of TPD. These policies currently insure 7.8 million people who hold them through their default super product.

It should also be noted that collectively the policies in our sample cover more than 75% of default product holders and 70% of default TPD policyholders throughout the MySuper period (2014 onwards).

As Figure 1 demonstrates, the vast majority of policies in our sample have used ADL type definitions since 2009. Based on group super claims data from 2018, ASIC estimates three claims a day are made under an ADL type TPD definition.

Considered together, these facts point to a long term, substantial detriment to consumers caused by discrimination based on work status.

Covid-19 has made it larger

In the context of increasing unemployment as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictive definitions are likely to apply to a larger group of policyholders. The ABS Labour Force survey shows the cohort of unemployed people increased by 211,000 between March and May.12

Many people are also working fewer hours than usual. Around 1.2 million people were working fewer than their usual hours due to economic reasons in May, up from approximately 390,000 in March.

The May RBA Statement on Monetary Policy baseline forecast for unemployment is 10% in the June quarter and they forecast it will remain above its March 2020 level until June 2022.13

Rising unemployment is linked to a higher insurance claims rate

Based on data from a number of countries, actuarial consulting firm Rice Warner has warned that disability and disability claim rates are likely to rise due to COVID-19 related job losses: “We know that disability claim rates are directly correlated to unemployment.”14

Many people’s policies become inappropriate once they are unemployed

The combination of much higher unemployment and a higher insurance claim rate will exacerbate the harm caused by restrictive terms. In our sample of 2020 policies, ten policies that collectively cover over 800,000 people have hours restrictions or unemployment terms that mean a restrictive TPD definition applies as soon as a policyholder becomes unemployed or works limited hours. We refer to these policies as “day zero”.

In response to our inquiries, BT, the wealth management arm of Westpac, has indicated they are planning to alter their policies such that they will allow a person to be unemployed for up to two years before a restrictive definition must apply. This positive development would if enacted reduce the number of “day zero” policyholders to 343,000.

Unemployment is likely to remain elevated for an extended period

The economy is unlikely to return to normal in the next twelve months, with the RBA baseline scenario predicting that unemployment will remain above its March 2020 level until June 2022. Thirteen policies in our sample that cover 615,000 policyholders will apply restrictive definitions to people who are unemployed for at least three months. Figure 2 shows how a person’s work status affects the likelihood they will be assessed under a restrictive definition.

Figure 2 - Infographic relating work status to requirement to claim under a restrictive TPD definition

Industry responses

Insurer response - A band-aid until 27 September

We note that the Financial Services Council recently announced all major insurers will allow people impacted by the pandemic to claim based on their employment status as of 11 March, until 27 September 2020.

It is good to see an acknowledgement that there is a problem with how these policies are designed. However, our research shows they have been relying on these discriminatory terms for at least 12 years, causing a substantial long term detriment.

By providing this relief only during the period where the JobKeeper wage subsidy still applies, insurers are containing costs as fewer people are technically unemployed as they receive JobKeeper through their employer.

The RBA is forecasting elevated unemployment until 2022, so once the JobKeeper payment period ends, more than 800,000 people in policies with hours restrictions or day zero unemployment terms will again be exposed to poor value insurance, should they become unemployed or fall under a minimum hours restriction.

Figure 3 - Infographic explaining how insurer relief period affects group super TPD claimants

Fund response - some positive steps, a long way to go

We wrote to the trustees of funds with particularly discriminatory terms in their default TPD insurance policies. These terms require policyholders to claim under a restrictive TPD definition as soon as they become unemployed or work less than a certain number of hours per week.

Table 6 details the funds we wrote to, the number of default TPD policyholders they have and their response to date.

Table 6 - Response from funds with particularly discriminatory policy terms

| Super fund | Insurer | TPD policyholders | Response to letter |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMP Funds | AMP Life | 67,362 | AMP has “developed a new design across all our products that aims to remove the hours test and also extends the period of unemployment to better align with the PYS [Protecting Your Super] period of inactivity [16 months].” AMP intends to implement these changes following formal approval in Q4 2020." |

| Equity Trustees (Aon) | AIA | 30,469 | AON Master Trust and the Trustee of smartMonday (Equity Trustees Superannuation Limited) has “commenced a comprehensive review of the fund’s group TPD Cover underwritten by AIA Australia Limited. That review aims to ensure that the insurance benefits offered to all members are appropriate both in terms of coverage and affordability.” |

| Intrust Super | AIA | 58,905 | Intrust did not respond to our multiple requests for a response by the date of publication. Intrust has since advised us that “The Fund has continued to enhance its TPD definition and a change is being implemented with effect from 1 October 2020. Our members, regardless of employment status e.g. Full Time, Part time or Casual (i.e. regardless of hours worked) will have access to claiming a TPD benefit which is assessed under the education, training and experience definition in circumstances where they have being gainfully employed within the 24 months prior to their Date of Disablement. After 24 months the ADW definition where they have not been gainfully employed will be utilised.” |

| LUCRF | OnePath | 76,486 | LUCRF “has also expressed concerns about the ADL test applied under one of our current TPD definitions” and is “presently in the process of considering the removal of the ADL test from our group life insurance policy”. LUCRF is “currently engaged in discussion with [its] insurer OnePath regarding [the ADL test] removal” and is “seeking to reach a position on the removal of the ADL test as soon as is practicable.” |

| PSSAP | AIA | 84,988 | CSC confirmed that the PSSap insurance policy prevents a member from claiming under the standard TPD definition if they have not been in gainful employment at any time during the three months prior to the date of disablement “however, every claim is still assessed individually and reviewed on its merits”. CSC also told us that it plans to conduct a policy review this year “at which time we will ensure terms reflect those customers with reduced working hours at time of disablement”. |

| BT (Westpac) | Westpac Life | 485,247 | BT have “a change being made effective 1 October 2020 which means members who are unemployed for up to 2 years will be able to claim under the standard TPD definition” |

| Suncorp | TAL | 25,683 | Suncorp has asked their insurer, TAL, to consider our call for ADL definitions to be removed from group insurance. Suncorp also told us that over the coming year they will be “reviewing the insurance offered to our members within our superannuation products. The review will focus on simplifying the number of insurance products and options available to our members, as well as improving the affordability of the insurance offerings. As part of this review Suncorp will engage further with TAL about the Activities of Daily Living requirements in its policy terms and conditions.” |

Conclusions

Widespread and long-standing detriment

Our research found that over 7.8 million Australians currently hold TPD insurance that has limited value if they become unemployed or work limited hours. Discriminatory terms in the policies require them to claim under more restrictive definitions of TPD than other policyholders.

Claims made under these restrictive definitions have a much higher claims denial rate than those made under a standard TPD definition (60% vs 12%). Despite this large difference in claims denial rates, people are charged the same premium regardless of the TPD definition they are assessed under.

We found that a large majority of default TPD policies in our sample of major funds have relied on these terms to discriminate against certain types of policyholders for at least twelve years, going back to 2009.

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a sharp rise in unemployment and reduced working hours, which is likely to heighten the detriment caused by these discriminatory policies.

Our recommendation: remove discriminatory terms and consider fair universal terms

In the short term we are calling on funds to remove these discriminatory terms from their policies. Longer term we support the Financial Services Royal Commission recommendation to explore the introduction of fair universal terms for default insurance in super.

As of December 2019 according to APRA ‘Life insurance claims and statistics database December 2019’. Available here↩︎

ASIC report 633 Holes in the safety net: a review of TPD insurance claims. Available here↩︎

The full list of superannuation funds in our sample is available here.↩︎

APRA Annual MySuper Statistics June 2019, Table 6. Available here.↩︎

On 1 April 2020, the Federal Government’s Putting Members’ Interests First (PMIF) legislation came into effect. It prevents super funds from providing insurance on an opt out basis to members who are under 25 years old and begin to hold a new product on or after 1 October 2019, and to members who hold products with balances that have never reached $6000. See here↩︎

Article by Daniel Herborn (Super Consumers Australia) ‘Industry offers temporary fix for junk TPD insurance in superannuation’. Available here↩︎

Productivity Commission superannuation inquiry report, section 5.1. Available here↩︎

Financial Services Royal Commission - Final Report, Section 5.2.1. Available here↩︎

Super Consumers and Financial Rights Legal Centre submission to Treasury Consultation ‘Universal Terms for Insurance in MySuper’. Available here↩︎

Disclaimer: The data on which this post is based was provided by Rice Warner Pty Ltd. All conclusions and commentary presented herein are based on the sole analysis, interpretation, views and opinion of Super Consumers Australia at Choice.↩︎

ASIC report 633 Holes in the safety net: a review of TPD insurance claims. Available here↩︎

RBA May statement on monetary policy, ‘Economic outlook’ section. Available here↩︎

‘Life insurance impacts in a pandemic’, Rice Warner blog. Available here↩︎